Chan-Hie Kim

Claremont School of Theology

Charles Maclay, the founder of the predㅗecessor school of Claremont School of Theology, was the brother of the man who paved the way for the American Protestant mission in Korea back in 1884. As is well known, the Claremont School of Theology was first established by Charles Maclay in 1885 as he donated 10 acres of land in the San Fernando Valley. The name of the School at the time was Maclay College of Theology. It is regrettable that this great man, the John the Baptist of the Korean Protestant mission, is least known among the Korean Christians. The importance of his work in the summer of 1884 is not properly recognized as it should be and even ignored by many Korean Church historians, particularly by the non-Methodists. Appenzeller of the Methodist Episcopal Church and Underwood of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America are prominent figures in Korea because they spent their whole life there. However, they are erroneously recognized as the first American Protestant missionaries in that country. It must be clearly said that it is not these two missionaries, but Robert Maclay who is to be recognized as the first official American Protestant missionary in Korea.

Thus the purpose of this paper is two-fold: first, to make it known that the Claremont School of Theology has a Korean connection right from the beginning of its opening, and secondly, to argue that Robert S. Maclay was the first official American Protestant missionary in Korea.

I

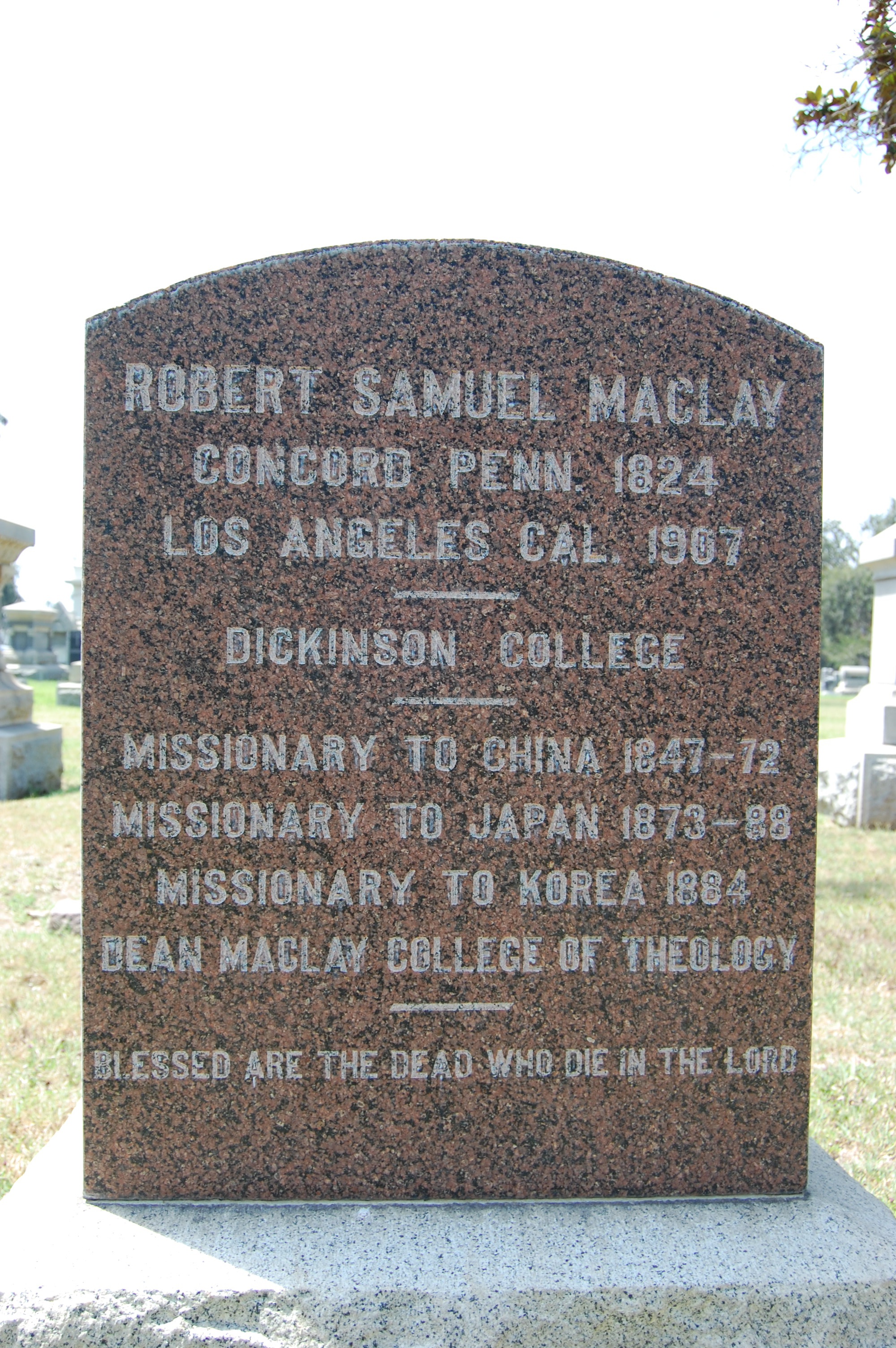

Robert Samuel Maclay was born in Concord, PA, February 7, 1824. He was two years younger than his brother Charles. He graduated from Dickinson College on July 10, 1845 receiving both B.A. and M.A. Dickinson College also honored him with D.D. later. He was received on trial in Baltimore Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1846 and was appointed missionary to China on September 10, 1847 by Bishop Hamline, which made him one of the first missionaries in China. He arrived in Foochow on April 14, 1848. He married Henrietta C. Sperry to whom he was already engaged in America as soon as she arrived in Hong Kong, July 5, 1850. She came to China as a missionary with an annual salary of $300 and outfit ($150) approved by the Board at the request of Maclay. She became a faithful companion of Maclay for the next thirty years. They had seven children between them. Since Maclay’s “unusual qualities of leadership” was soon recognized, the Church appointed him superintendent and treasurer of the China Mission on March 31, 1852. He held this position until November 16, 1872 when the Church transferred him to Japan and appointed him superintendent of the newly opened Methodist Mission there. He arrived in Japan on June 11, 1873. He published much needed and significant literature both in Chinese and Japanese. He was good at these languages and they became important courses at the Maclay College of Theology. Soon after he had established the Korea Mission in 1885 he retired from his long career as a missionary in Asia, he was appointed Dean of Maclay College of Theology on April 30 and was installed on September 18, 1888. He remained in this position until 1901. The pioneer and founder of the China, Japan and Korea Missions of the Methodist Church died on Sunday morning, August 18, 1907 in Los Angeles at the home of his nephew, Dr. J. P. Widney, at the age of 84.

It is to be noted that the School has opened the Center for Asian-American Ministries in 1977, which would not only help the Asian-American constituency of The United Methodist Church but be an advocate for theological as well as ministerial needs of the Korean-American churches. It seems to be God’s providence that the institution which was established by the brother of the person who knocked the door of the “Hermit Kingdom” and opened it now serves the very people he helped hear the good news. Robert Maclay might not have imagined this could happen almost one hundred years later. It must be said at the outset that Robert Maclay was not merely related to the School through family connections, but he himself served as the second dean of the School from 1888 until 1901 when the first dean, R. W. C. Farnsworth died within a year after the School opened the first class of ten students October 5, 1887.

II

It is necessary to be informed about the historical situation, particularly the diplomatic relationship between Korea and the United States, in order to understand the motive and circumstance of Maclay’s visit to Korea.

Under the sound of a verse of “Yankee Doodle” the formal diplomatic relation between Korea and the United States was first established by signing an amity and commerce treaty commonly known as the “Treaty of Chemulpo” by the Koreans. The treaty officially known as the “Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States of America and Corea” was signed on May 22, 1882. This treaty was the first in the series of friendship and peace treaties Korea had ever made with the Western nations. It was sent to President Arthur and then to the U. S. Senate on July 29, 1882 and was ratified on January 9, 1883. The treaty was proclaimed on June 4, 1883. It was the fruit of Admiral Robert Wilson Shufeldt’s effort to open the door of this “Hermit Nation.”

Adm. R. W. Shufeldt’s involvement in this diplomatic negotiation traces back to the summer of 1866 when Korean soldiers destroyed an American merchant vessel, General Sherman, on Taedong River. When the news of this tragic incident reached the American squadron in China commanded by Adm. Bell, Adm. Shufeldt who was then in command of USS Wachusett harboring in Hong Kong was dispatched to Korea to investigate the incident on January 21, 1867. But before he had completed his mission, he was ordered to return home. In an article he wrote for the Korean Repository (February 1892) he wrote: “Our intercourse with the natives was not of an unfriendly character…. From that moment, however, I conceived the idea and considered it possible to make a treaty with this Hermit Nation without the exhibition of force.”

A few years before Shufeldt was able to negotiate the treaty with the Korean government, the U. S. Senate passed the second reading of a resolution submitted on April 8, 1878 by Senator Aaron A. Sargent of California urging the President of the United States to “appoint a commissioner to represent his country in an effort to arrange, by peaceful means and with the aid of the friendly office of Japan, a treaty of peace and commerce between the United States and the Kingdom of Corea.” Unfortunately, however, the resolution did not materialize because the congress adjourned before it took the final action.

Meanwhile, in the fall of the same year, that is, on October 29, 1878, when the Unites States Navy sent Shufeldt “around the world on a commercial and diplomatic mission,” R. W. Thompson, Secretary of the Navy, specifically instructed the admiral to “visit some part of Korea with the endeavor to open by peaceful measures negotiations with the government” during the course of the worldwide cruise. Now his dream to make a treaty with Korea which he had since the General Sherman incident of 1866 was about to be realized. When he arrived in Japan in April 1880 and sought help from the foreign office for a visit to Korea, he was not able to get much help from this “friendly office” as L. G. Paik describes. But his effort in Japan was not entirely fruitless. Through his personal acquaintance with U Tsing, a Chinese consul at Nagasaki, he was able to make a contact with Viceroy Li Hung Chang who was one of the most influential officials in China on foreign affairs. When Li learned that the United States was interested in making a treaty of peace and commerce with Korea through Japan, he was alarmed. He was afraid that the combined forces of Japan and the United States, one of the most powerful Western nations, would threaten the security of China. So China wanted to get involved in this negotiation, particularly to minimize the influence of Japan on the Korean peninsula.

We need to note that the last decades of the 19th century was a period of the “Korean tangle.” Russia, China, and Japan were fighting for the hegemony in Korea. This powerless Kingdom of Korea became the battle field of these powerful nations for, in the words of A. J. Brown, “the Korean Peninsula is the strategic point in the mastery of the Far East.”

Li invited Adm. Shufeldt to China to mediate the treaty between the United States and Korea. The treaty was negotiated between Li and Shufeldt without the presence of the Korean delegates. The treaty was finally signed by the Korean officials, Shin Hun and Kim Hong-jip, and Shufeldt. Shufeldt recounted this historic event in the history of modern Korea as follows:

A few days afterward (1882) the Koreans having provided a tent upon the point at Chemulpo, I landed with a staff of officers and a small guard of men. Having peacefully planted the American flag before the tent, to the tune of ‘Yankee Doodle,’ I signed the first treaty ever made between the Hermit Nation and any Western power…. It was as easy a thing to do as for Columbus to stand his egg on end.”

Maclay later made the following confession on the event:

The negotiation by Admiral Shufeldt of this treaty with Korea was a trumpet call to immediate efforts for the evangelization of the Korean nation which Protestant Churches, and in particular the Methodist Episcopal Church, could not suffer to pass unheeded.

American presence in this helpless Kingdom did make a difference in power dynamics at the time when China, Russia, and Japan were making aggressive advancement in Korea. Interestingly, the same power game is still going on in this part of the world today.

Shortly after the treaty was signed by both nations, the American government dispatched General Lucius H. Foote to Korea as the Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary. He was appointed to the post on March 7, 1883 and arrived in Seoul on May 13, 1883. He was cordially accepted by the King and queen of Korea. When Maclay had planned his visit to Korea and actually arrived there, Foote was the one who gave him much needed advice on all political as well as other practical matters of logistics. Not only that, he was also very supportive of all the earlier American missionaries from the United States.

Since Korea was in political turmoil in the 1880s, Gen. Foote’s assistance was imperative. The late 19th century in Korea is known as the “Period of Enlightenment,” for modern Korea emerged during this period–the period when Korea was wakening up from a long sleep by opening its door toward other nations, particularly the Western countries. Consequently the collision and struggle between the conservative forces and the progressive party over political hegemony was inevitable, which finally led to the abortive bloody coup d’état on December 4, 1884 (Kapsin Chongbyun) staged by members of the progressive party. I mention this incident because Robert Maclay got acquainted with those leaders of the coup while in Japan, and the key leader, by the name of Kim Ok-kyun, was the man through whom he received the permit from King Kochong to open the medical and educational “mission” in Korea. Maclay gave him the credit for his work: “In July, 1884, he [Kim Ok-kyun] had called on Mrs. Maclay and myself during our visit to Seoul, and it was due almost entirely to his efforts that, with God’s blessing, the King of Korea gave his permit to Christianity in response to our petition.” Maclay later wrote about his tragic assassination in one of his articles on Korea.

III

Geneneral Foote was welcomed by the Korean government with great enthusiasm because the establishment of the legation symbolized the declaration of independence from China breaking the centuries old vassal relationship with her. The establishment was a glad tiding for the Korean people who had been under the dominion of China for many centuries and harassed by the Russians and Japanese in recent years. It was an indication that Korea was no longer a vassal kingdom but a nation with integrity and sovereignty. It was even “reported that the King ‘danced for joy’.”

In response to the opening of the legation and as an expression of her appreciation to the United States, the government of Korea decided to send an eight-member embassy to America headed by Min Young-ik, one of the high-ranking officials and a nephew of Queen Min. Hong Young-shik was appointed as deputy.

This embassy left Chemulpo (Inchon) on board the Monocacy, a US merchant vessel, on July 16, 1883. The ship was arranged by Foote. In Yokohama, Japan they were joined by two more additional interpreters, Percibal Lowel, an American whom Min appointed as Foreign House Secretary and Foreign Secretary to the Embassy, and a Japanese interpreter, Yamaoka. On August 11, 1883 they continued their journey on board a steamer Arabic to San Francisco where they arrived around noon September 2, 1883. They left San Francisco for Washington by train on September 4. It is reported that they were cordially accepted in Washington by President Arthur.

Another chapter in the history of American Protestant mission in Korea was on this train. Whether it was a coincidence or providence, the embassy met a gentleman from Baltimore who would later sponsor Maclay’s visit to Korea so that he might explore a possibility of Methodist mission there. The Reverend Dr. John F. Goucher, a Methodist minister burning with the zeal for foreign mission, who later became president of Goucher College in Baltimore, happened to be on the same train with the Korean embassy. During the next three days while traveling together for Washington, Goucher learned many things about these strange people from the Orient. He was excited about the possibility of a mission in the Hermit Kingdom. He invited Min Young-ik and his company to visit him when they get to the Washington-Baltimore area. Perhaps he had already made up his mind to initiate some mission work in Korea during this time while traveling with them. It was impossible to quench the burning fire within him to expand the kingdom of God to the end of the earth.

IV

Almost two months later after returning from a trip to the West, on November 6, 1883, Goucher, “a leading Board member of the Methodist Missionary Society,” wrote a letter to the General Missionary Committee of the Methodist Episcopal Church requesting to “aid in commencing missionary work in Korea.” He offered $2,000 for the initial work. He added further, “In my judgment our church should enter that field with evangelistic, educational, and medical agencies at the earliest possible moment.” One week after receiving Goucher’s letter the General Missionary Committee voted that “$5,000 be appropriated to the Japan Mission for the purpose of opening Mission Work in Corea of which $2,000 is a special donation by Rev. J. F. Goucher.” In the fall of 1884, after Maclay returned to Tokyo, he offered an additional $3,000 “to be used in purchasing a suitable site for our mission operations in Seoul.” L. G. Paik, however, stated that Dr. Goucher “failed to receive encouragement from the mission board. Thereupon he wrote on January 31 of the following year [1884] to Robert S. Maclay.”

Whatever it might have been, this anxious servant of God contacted Maclay who was serving then as the superintendent of the Methodist Mission in Japan. He sent a letter to Maclay dated January 31, 1884, saying,

Under date of November 6th, 1883, I wrote to the Missionary Committee that if they deem it expedient to extend their work to the Hermit nation, and establish a mission in Korea under the superintendence of the Japan mission,…I shall be pleased to send my check for, say, two thousand dollars toward securing that result.

Could you find time to make a trip to Korea, prospect the land, and locate the mission? For once we may be the first Protestant church to enter a pagan land. It is peculiarly appropriate that Japan should have the honor, and it would be a fitting addition to the service you have been enabled to render your church already if you could inaugurate the enterprise.

Maclay received this letter in March 1884 shortly after he moved from Yokohama to Tokyo to assume the presidency of the Anglo-Japanese College, now known as Aoyama Gakuin University. In fact, it was Dr. Goucher that proposed the establishment of this college first in 1882, and sent gifts for it. Maclay was the founder and the first president of the college. According to the Methodist Annual Report of 1881 (p. 204) and 1882 (p. 142), Goucher donated initially $5,000 for the purchase of the property and then “$800 a year for five years toward the salary of a Japanese professor.” Goucher had already made some financial contribution towards the work of Japanese mission in 1881. Not only that, he also supported the work of mission in India.

Since he had already such a rich experience in pioneering mission work both in China and Japan, it was certainly a great challenge for him. He had full confidence that he could carry out the mission. The letter, Maclay felt, was another call from God to move on to another mission field. He recalled the event and described his feelings in San Fernando as follows: “This letter from Dr. Goucher opened the way for the accomplishment of a long-cherished desire, and impressed me at once as being a Divine call to do what I could toward opening Korea to Christian mission.” The letter enabled Maclay to realize the long-waited dream he had kept ever since he saw a few ship-wrecked Koreans for the first time in the streets of Foochow while stationed in China. He recalled again, “Their [Koreans] strange costume, erect forms, and agile movements greatly interested me, and I felt it would be a high privilege to carry to the people of Korea the precious tidings of salvation.”

V

With the enthusiastic support and endorsement of the Japan Mission and the missionary society, Maclay was ready to make his trip to Korea. After checking with John A. Bingham and Lucius H. Foote, the U. S. Ministers to Japan and Korea respectively, about the feasibility of the journey, he embarked accompanied by his wife on board the English steamer Teheran at Yokohama on June 8, 1884. When Dr. and Mrs. Maclay made their first stop in Nagasaki, they hired a Korean interpreter. Here they left Teheran and on June 19 they sailed on board the steamer Nanzing toward Chemulpo (Inchon), a port near Seoul where the first Korean-American treaty was signed as noted above. Next morning, they were in the territory of Korea making a call at Pusan, a port city in the southern tip of the Korean peninsula.

It is interesting and amazing to note Maclay’s profound historical knowledge on the relation between Korea and Japan. What he knew then is not well known among the contemporary Japanese intellectuals. It is even concealed in the official history books of Japan today. Namely,

Fusan [Pusan] is a place of historic interest and commercial importance. It is not improbable that from it sailed the bold clans who conquered and whose descendants still hold Japan. Certain it is that here landed the military expeditions of the Japanese, which from early centuries of the Christian era have harassed and overrun Korea. It was pleasant and assuring to think that in our day there came from the shores of Japan those who desire to give the Koreans the tidings of salvation through faith in our Lord and Savior.

He was very much aware of that the Japanese imperial family and ruling classes were originally from Korea and that the Japanese had constantly harassed the Koreans whenever they had the upper hand. It is also interesting to note that he believed the good “tidings” came from Japan rather than from America as Koreans believe.

After spending forty-two hours in the Yellow Sea (the sea between China and Korea), the Maclay party reached Chemulpo at 1:00 p.m., June 23, 1884. On the following morning they departed for Seoul which is located about 25 miles from Chemulpo. They entered Seoul around six p.m. on the same day greeted by General and Mrs. Foote of the US legation in Seoul. They stayed in a small building close to the legation ground. Before his departure from Seoul, he asked Gen. Foote to purchase the building for the use of Korea Mission, but the transaction did not materialize immediately.

VI

One misfortune the Maclays experienced in Korea which turned out to be rather a fortunate incident was that their interpreter whom Maclay procured in Japan left them because he was afraid of being attacked by his fellow conservative party members. Even though the government was under the control of the Progressive Party at the time, there still was a strong opposition from the conservative party which was supported by China. Politically, Korea was going through great turmoil. The struggle for hegemony between these two antagonistic parties each supported by the foreign powers, China and Japan, made the situation worse. Thus an association with Westerners could easily cause suspicion.

The loss of a helper was the gain of an ally for Maclay. As Maclay quoted

old proverbs such as “At evening time it shall be light” and “Man’s extremity is God’s opportunity” in his article, he “providentially” met Kim Ok-kyun with whom he and Mrs. Henrietta C. Maclay “had formed a very pleasant acquaintance in Japan.” As mentioned earlier, Kim Ok-kyun was the key leader of the progressive party now serving as a government official. Thus, there was no need of an interpreter for Maclay because he could converse with Kim Ok-kyun in Japanese. He could communicate with Kim better without an interpreter for here was a man who was well acquainted with the wishes of this guest from America. Moreover, even though he himself was not in favor of propagating the new religion in Korea, Kim was very much aware of the benefits this mission would bring to a nation in urgent need of reform for modernization. Through his visits to Japan (at least three times) he had seen what the Meiji Restoration brought to Japan, namely, modernization and, to a certain degree, Westernization of the Japanese political and economic systems as well as social life. He had also seen many humanitarian works carried out by the American missionaries.

About a week after he arrived in Seoul, on June 30, he forwarded a letter written in Japanese to Kim Ok-kyun to be presented to the King. The full content of the letter is not known for Maclay did not reveal any details except that he requested the King to grant a permit for “medical and educational” work in Korea. It seems to be clear that Maclay was aware of the government policy of prohibiting propagation of the Christianity. This policy was not enforced by the government even though the subsequent missionaries were involved in doing “religious” work. The Korean government tacitly allowed the missionaries do the evangelistic work shortly after Maclay left.

Maclay told Kim that his time was very much limited, and requested him to expedite the process. He trusted that Kim “would do everything in his power” and help the King make favorable decision on his behalf. He seems to have even known what an important position Kim occupied in the government, the chief assistant to the King, so to speak. After waiting a few days for an answer, he “ventured to call on him July 3rd.” Maclay further reported,

He [Kim Ok-kyun] received me very cordially, and at once proceeded to inform me that the king had carefully examined my letter the night before, and in accordance with my request had decided to authorize our society to commence hospital and school work in Korea. “The details,” continued Mr. Kim, “have not been settled, but you may proceed at once to initiate the work.” The king’s favorable response to our appeal was so prompt and complete, that I could not fail to recognize it as from the Lord, and after tendering to Mr. Kim hearty thanks for his good offices in our behalf, I took my leave, repeating to myself, as I rode through the crowded streets of the city, “The king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord, as the rivers of water. He turneth it whithersoever He will.”

This date, namely, July 2, 1884, is to be marked as the official beginning of the Protestant mission in Korea. Maclay further related that Kim called on him in that afternoon and congratulated him on his successful appeal. Just before his departure for Japan, he made an arrangement with Minister Foote to purchase the building he and his wife occupied during their stay in Seoul for the soon-to-be established Korean Methodist Mission. He did not forget to give credit to Dr. Goucher for his successful trip to Korea by saying, “The opportune proposal of Rev. John F. Goucher, D.D. of Baltimore, to give liberal aid in founding the Korea Mission, was cordially accepted by the missionary authorities of our Church. My visit to Seoul was the result of this proposal; and thus it became my high privilege to lay the first foundation for a Christian mission in Korea.” His party left Seoul July 8, 1884 to go back to Japan.

It is apparent in his writings how much he regretted not being able to enter a new field of mission after such a successful work well done in China and Japan. His failing health and age and the work just begun for the Anglo-Japanese College did not allow him to go to Korea. His nostalgic feeling is eloquently expressed in the following paragraphs.

Cheered by the royal permission to commence Christian work in Korea, I could have wished to enter at once upon the enterprise which for years had received my attention, for the initiation of which the way was now prepared, and for whose effective prosecution a willing and loyal constituency stood ready to furnish the necessary support. After having been associated with others in efforts to plant and train our branch of Christ’s Church in China and Japan the opportunity now presented to perform, under the most favorable auspices, a similar service in Korea so attractive that I almost chided myself for not having tried to make arrangements to this effect before entering on the present trip.

Reflecting on his past achievements and experience, he continued on to say,

…while coveting the best gifts, the ‘more excellent way’ for me would be to yield to others the honor of entering this open door, and content myself with the duty of giving such advice as experience, my position in Japan, and my official relation to the Korean Mission might enable me to offer.

Satisfied, but not jubilant, I accepted this post of duty, and until my return to the United States at the beginning of 1888, endeavored, to the best of ability, to aid the devoted and successful laborers whom the Church appointed to cultivate this field, over whose broad acres I would gladly have scattered the seed of the kingdom, and into whose golden harvest it would have been an inexpressible joy to thrust in my sickles.

This old veteran missionary had to yield this great opportunity and honor to the 26 year old young man from Souderton, PA, Henry Gerhard Appenzeller and his wife (Ella J. Dodge), Rev. William Benton Scranton, M.D. and his wife (Loulie Wyeth Arms), and Mrs. Mary Fitch Scranton, mother of Dr. Scranton. The Appenzellers set their feet on the soil of Korea along with another missionary, Horace G. Underwood of the Presbyterian Church, on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1885. Dr. Scranton followed them arriving there May 3rd even though he was appointed to be a missionary a couple of months earlier than the Appenzellers. A host of missionaries from America, England, Australia, and Canada entered this new “golden harvest” field in subsequent years.

VII

It is significant to note that the opening of the Methodist Mission in Korea coincides closely with the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States.

When the newly appointed Methodist missionaries were about to enter the new mission field in Korea, Maclay received a letter on March 31, 1885 from Bishop C. H. Fowler of San Francisco dated February 23, 1885 concerning the organization of the Korea Mission. The letter read: “We desire you to act as superintendent of Korea and Brother H. G Appenzeller as assistant superintendent under your direction. Dr. Scranton will act as treasurer of Korea Mission.” Thus, the official Methodist Mission for Korea was duly organized. The appointment of Robert S. Maclay by the bishop makes him not only the first missionary but the first superintendent of the Korea Mission.

The first meeting of the missionaries appointed to Korea was held in Aoyama, Japan, March 5, 1885, at Maclay’s study before the letter from Bishop Fowler reached Maclay. The minutes of the meeting are as follows:

THE MINUTES OF THE FIRST MEETING OF THE

MISSIONARIES TO KOREA

Aoyama, Tokio, Japan. March 5, 1885.

In Rev. Dr. Maclay’s study.

Rev. R. S. Maclay, superintendent of the Mission, presided at the meeting and conducted the religious exercises, reading Psalms 121; 122. Hymn number 547, “A charge to keep I have” was sung and prayer offered by the President. Dr. Maclay then gave us a hearty welcome and God speed to our new field of labor, concluding with a short account of his visit to Korea in June, 1884. General discussion of the prospect of the work followed the address. Adjourned to meet at 2 p.m.

Reconvened at 2:45 p.m. with Dr. Maclay in the chair. Moved that $200.00 be set aside from the money appropriated to school work in Korea for the support of four Korean students in the Anglo-Japanese College at Tokio to the end of 1885. Moved that

Dr. Maclay be authorized to publish the Methodist Catechism, No, 1 in the Korean language; also Mr. Rijutei’s [Yi Su-jong]] translation of “Easy Lesson in the True Doctrine.” Ordered to appropriate $250.00 from the school fund for the translation and publication of the tracts and hymns.

Adjourned to meet at the call of the President.

H. G. Appenzeller, Secretary

Missionaries present at this meeting, Dr. R. S. Maclay, D.D., Rev. and Mrs. H. G. Appenzeller, Dr. and Mrs. W. B. Scranton, and Mrs. M. F. Scranton of the W.F.M.S.

Present were also Yi Su-jong and Park Young-hyo at this first meeting of the missionaries to Korea.

If Maclay had received the appointment letter from Bishop Fowler just two weeks earlier, this meeting could have been called by the newly appointed superintendent, Robert S. Maclay, rather than in the name of the superintendent of the Japan Mission, and thus become the first meeting of the Korea Mission ever convened. However, since his appointment was made on February 23, 1885, two and a half weeks before the meeting, we may be allowed to call it the first official meeting of the Korea Mission. Maclay held this position until 1887, just before he retired from his work in Japan and came to San Fernando to assume the deanship at the Maclay College of Theology.

Even though Robert Maclay was not able to be physically present in Korea to carry out his new responsibility as the superintendent of the Korea Mission, it is apparent that he is a pioneer and the first Protestant missionary openly to enter Korea with the permission from the government. This does not deny by any means sacrificial and efficacious efforts and attempts by other pioneering Western missionaries to open the door the Hermit Nation prior to Maclay’s successful mission. Their contributions and services are well documented and shall never be forgotten by the Korean Christians.